VILLAGE HEALTH COUNCIL

Village Health Councils (VHCs) were notified by the Government of Meghalaya in February 2022 as the nodal community institution to “mobilize actions on health and nutrition issues and serve as a critical link between the state health systems and community members

From every ten households, one representative is chosen, encompassing both male and female heads of households in a village.

An elected executive committee, comprising a minimum of ten members, provides leadership. Half the seats of the executive committee are reserved for women.

The local Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) and Anganwadi worker (AWW) are also permanent members of the VHC. Teachers from local schools and community gender and health activists are part of the VHCs wherever possible. VHCs meet at least once a month to discuss health and nutrition issues important to their community.

Role of Village Institutions

The idea of setting up community-level institutions to solve health issues is not entirely new. Village Health, Sanitation, and Nutrition Committees (VHSNCs), implemented as part of the National Rural Health Mission, were created as organizations empowering community members to independently address health, nutrition, and sanitation issues without external intervention.

However, they suffered from many problems: irregular and unplanned meetings, low attendance; and unclear roles and responsibilities of members.

Success was seen through Meghalaya’s community-driven actions during the COVID crisis, where

7,000

community COVID management teams were established in 2 weeks.

Premised on the idea of positive health

VHCs attempt to solve many health issues at the community level. For example, community members persuade pregnant women to register for antenatal care and help arrange transport for institutional deliveries. Likewise, they collectively take responsibility for mobilizing men — who may be hesitant — to seek treatment for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as hypertension or diabetes.

As mentioned earlier, connectivity issues and geographical terrains make it arduous for healthcare workers to reach remote villages. VHCs are being empowered to solve some of these challenges. For instance, the Pradhan Mantri-Ayushman Bharat Health Infrastructure Mission (PM-ABHIM), a centrally sponsored scheme of the Government of India, seeks to improve public health infrastructure across the country. One of the key components of the Scheme is the construction of health sub-centres in rural areas.

The government of Meghalaya has empowered the VHCs to take on the work of constructing these sub-centres in their villages. As a result, VHCs have been able to bring health facilities to their communities, even when they cannot go to them.

The hope is that such initiatives will help build the capability and confidence of VHCs to take ownership of other health and nutrition issues that matter to their communities.

VHCs incorporate local realities

Meghalaya, a Sixth Schedule state, has had strong community institutions for centuries. VHCs seek to include these existing institutions.

The village headman, who enjoys considerable local authority, is appointed as the chairman of the VHC. Similarly, the co-chair position is reserved for the president of the village organization (VO), which is a federation of women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs).

The inclusion of these existing institutions and traditional sources of authority within the VHC ensures their legitimacy. These community leaders are able to mobilize their communities’ health-seeking behaviour.

Initiation and Way Forward for VHCs

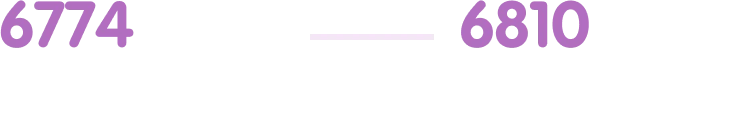

VHCs have been formed in a majority of Meghalaya’s villages. According to state government data

which covers over ninety-eight percent of Meghalaya’s villages. However, ongoing efforts are being made to strengthen VHCs, particularly in terms of regular meetings. As of January and February 2023, fifty-three per cent of VHCs have already conducted meetings. Handholding and further strengthening are essential for the long-term vision of building sustainable practices.

The Meghalaya government has better-equipped VHCs to meet more regularly and have better discussions during meetings. The tools include a VHC Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) book to help communities learn about different health and nutrition issues, a VHC Register where communities can record minutes of VHC meetings, and actionable steps they plan to implement.

The government has also introduced a VHC App, accessible offline, which will serve as a common interface. It not only enables direct communication and information sharing within the VHC network but also provides real-time insights to State and Block functionaries.

Through institutions like the VHCs, Meghalaya as a State is actively empowering communities to identify local problems and constantly innovate to highlight and solve them.